At the peak of my stress and worry last week, i muttered “life is so hard.” My wife Cheryl reminded me “it doesn’t have to be.”

But i’m the type of guy who charges over (or through) the mountain instead of taking the footpath that winds pleasantly around it. The latest mountain i scaled was launching LockQuest, a brand new real escape the room game company in Toronto. It’s probably the most difficult thing i’ve done in my entire life, and that includes running my boutique video game studio Untold Entertainment. The two companies require similar skillsets to a point, but when they diverge, they do so radically.

Back to Life. Back to Reality

LockQuest creates immersive, real-life game experiences that see players locked in a room for one hour. They have to collect clues and solve riddles and puzzles to find the front door key and escape. Each game is personalized and customized to the team of players, resulting in a game that’s uniquely tuned to its players’ proficiency and ability. In short, if you came to have fun, you’re in the right place. We deliver the fun.

Designing and building a real escape the room game here in Toronto was fascinating, fun, and frustrating all at once. Of course, i drew on my fifteen years of experience as a professional game developer to plan out the lock-and-key structure that players would navigate to win the game. That was actually the easy part! The first LockQuest game, Escape the Book Club Killer, was designed in a single evening.

The hard part was everything else. There are enough differences between developing a physical game vs designing a virtual game that i thought it would make an interesting article. Here, then, are those differences.

Drawing Something is Way Faster and Cheaper than Building Something

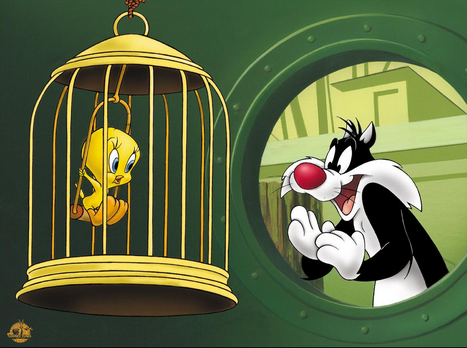

The birdcage. My friends got pretty tired of me complaining about all my birdcage travails. The story is that Escape the Book Club Killer features a birdcage, and aesthetically, i wanted it to look like – you know – a birdcage. The most birdcagey-birdcages i could imagine were made of black wire or metal. They were tall and skinny, and had a domed top. i was picturing the kind of thing you’d see Tweety Bird hanging around in.

The problem with having 1930’s Looney Tunes animations as your only frame of reference for the real world is that the objects they depict are all of that same 1930’s vintage. You don’t simply buy a black wire dome-top birdcage any more. You got a bird? You buy one-a deese:

Anyone with an artistic eye will see pretty quickly that modern birdcages lack the appeal of more classic designs. So what do you do?

If you’re making a video game, you say to your artist “Draw me a birdcage.” With any luck, he or she will draw exactly what you were picturing, and it’ll take a couple of hours. At the absolute worst, you’ll have to supply that picture of Tweety Bird and specify “one of those dome-topped 1930’s jobbies.”

With a live escape game, you have two choices: you either go shopping, or you fabricate the thing yourself. And since i’m rather unacquainted with TIG welding and working with raw steel, i decided on the former.

i hit up the usual suspects first: Craigslist and Kijiji. i quickly learned that photographers and wedding planners hog all the good, pretty birdcages, snatching them up before anyone else gets a chance, and then they rent them out for weddings so that people can put money-stuffed cards in them.

Tangential rant: people on Kijiji don’t know how to price things to sell. They always want to charge you 85-90% of what they paid in-store 5 years ago. And if you get a response from a poster, you’re lucky. And if you post a “WANTED” ad with a bunch of photos of the kind of birdcage you’d like to buy, you’ll get people writing you up saying “i’d like to buy these birdcages from you.” Sigh.

Birdhunting

So my wife and i rented a car. We hit up every Value Village (a thrift store chain) in the Greater Toronto Area – something like eight stores. We careened through every flea market in the area. We hit up pet stores, furniture stores, and Habitat for Humanity ReStores – again, every single branch in the area. We scoured both individual antique stores and sprawling antique markets. In the end, we had rented vehicles across three successive weekends, and had picked through literally fifty different stores in our search for a dome-topped birdcage. The development cost between this process and getting a game artist to bend a few splines in Adobe Illustrator is stark.

In the end, i finally found my dome-top birdcage at HomeSense of all places, which i liken to scouring the globe for the Holy Grail only to discover it in the discount dishware bin at Dollarama. You can see the precious cage tantalizingly out of focus in the background of this “screenshot” of Escape the Book Club Killer at LockQuest:

Testing the Game is Far More Risky

We have this concept in video games called the “stick-and-ball” or “alpha” version. At that milestone, the game is playable and you can get a sense of the main mechanic (the central action you take to play the game), but the graphics may be laughably bad. Our term “programmer graphics” describes a situation where a non-artist has slammed in some rough doodles just to get the point across.

An early screenshot from Spellirium lacks a certain … je ne sais quoi.

You test, iterate, and refine. Those fancier graphics come, but depending on the game, they can be introduced at a fairly late stage.

With a real escape game, so much of the experience is tied up in your props and sets that you basically have to spend all your money on the “graphics” and have them in place before you can test the thing. The “mechanics” of the game come next, so the process is effectively backwards. And you run a real risk of spending money on a prop for a puzzle that just doesn’t work.

Going back to the birdcage example, you might think “well, the ‘programmer graphics’ version of that is to buy a cheap, modern birdcage and swap it out later.” That’s what i thought too. But if you’re like me, a landlocked urbanite with no vehicle and no easy access to yard sales, the cost of a modern birdcage is about two hundred dollars. The cost of our hard-won fancy birdcage is about the same. Often times, testing with a less-than-ideal prop would cost as much or more time and money as just doing it the right way to begin with.

Maybe you can buy props from stores that have merciful return policies, but you have to get all your testing done within that policy window, or you’re stuck with those items. You can try to alpha it by rushing in during gameplay and telling your players “see these two pieces of paper you’re holding? One is going to be a big brass sun with hieroglyphics engraved on it, and the other is going to be a ceramic elephant filled with sparkly gems.” But the game just loses so much when you don’t have those tactile props. If you’re testing with paper, it won’t have the right feel. It defeats the purpose entirely. You might as well be testing a board game.

We DID paper prototype prop locations for the game, to ensure we had everything in the right place. (This is not a picture of OUR paper prototype, because secrets.)

Playing is Absolutely Unforgiving

i’ve had the experience, many times, of sitting a player down in front of my video game and watching those first few moments unfold. My heart was in my throat, my palms were sweaty, and i desperately wanted the player to laugh in all the right places, pick up on all the clues, find all the things, and have a good time. But i always knew that if a play session didn’t go well, i could blame the fact that maybe it wasn’t the player’s favourite genre, or that the game would take a little more time to “click” for that player than our demo session allowed.

That player probably prefers first-person shooters anyway.

In a live, physical escape game setting, all bets are off. These people have already paid their money, and you MUST make sure they have a good time. If a prop breaks in the middle of the game, or if you forgot to lock a door, or if the players decide not to engage with your giant prop jar of human hair, it’s now YOUR problem: your immediate problem that you have to fix in the next five-to-fifteen seconds.

The whole thing takes on much more of an air of live theatre. Indeed, when i went looking for employees, i made sure that “improv experience” was right there in the title of the job posting. The secret to fixing the game on the fly is to ensure that you have enough creative avenues to control the action, while still making it feel like it’s all part of the show.

It’s a feature, not a bug. You’ve unlocked … uh … the ALIEN basketballers from Space Jam.

At LockQuest, we can telephone players in the room in character to subtly hint at something they might have missed. We can slide mail and other hinty printed objects under the door. In absolute crisis mode, we can sneak into the room to fix, say, an accidentally unlocked door, but we can do so in ninja gear.

Did we forget to hide a puzzle piece?

These Physics are Astonishingly Believable

Building and running a live escape game is a world apart from developing a virtual video game, but in both cases, the real hard work comes after that euphoric honeymoony design stage. With video games, you can solve most of your problems sitting on your duff in a wheeled chair. With physical escape games, it’s “have design, will travel:” your design adventure, along with your game, exist entirely in meatspace, and you have to be willing to go the physical distance to make it all come together.

Tickets for Escape the Book Club Killer are now available for November and December at LockQuest in Toronto.

Dear Mr. Ryan,

In Turkey escape room started about 5 months ago, and expanding dramatically. Without any advertisement, with only word of mouth it easily became craziness. Also when i digget in to budget and cost calculations i can see a great oppurtunity of business.

As i explored escape rooms in here Istanbul, i found out many missings which you mentioned in your article. As i read it, we have similar approachs about story and story related riddle. Escape rooms here just have an attractive name but including inrelevant ridles and puzzles. There is no relation with story and stories are so weak.

With your approach we can create big potential here. I would like to learn that are you offering guidance services about concept and riddles professionaly? If yes, i would like to hear about your proposals and costs about it?

Looking forward to hear from you

Best Regards

Gorkem Kutlu

Hi, Gorkem. Please email me at info@lockquest.com and we can discuss!

– Ryan