Don’t SaaS me, software developers. i’ve seen through your little scheme, and i want no part of it.

Within the past 10 years, two horrid monetization models have emerged for software. The obvious one is much-harangued microtransaction model popular with video games, where the player pays small sums of money to access in-game rewards and googags. Those small sums often add up to large sums, and the kids of unsuspecting parents end up getting grounded, and saddled with a huge repayment plan.

Sorry, Mummy – i just HAD TO HAVE DEM SMURFBERRIES

The other model hasn’t come under the same scrutiny, and has instead been given a cutsey acronym and is thrown around tech conferences like it’s the Second Coming: Software as a Service. SaaS has customers paying monthly. We used to call that a subscription model, but somewhere along the line (possibly due to customer aversion or its association with the doomed world of print), “subscription” became a dirty word. Now it’s called SaaS. Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.

Mo(nthly) Money

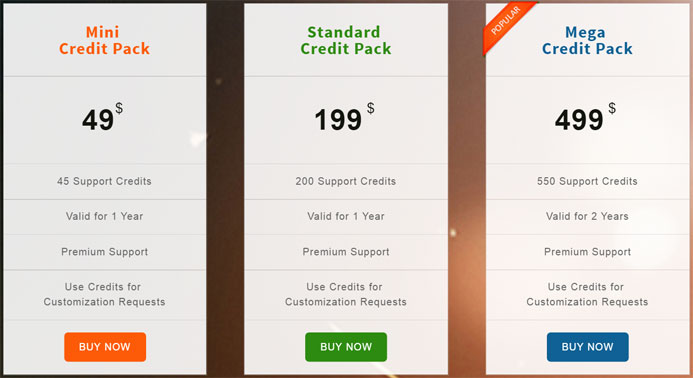

The upside of SaaS for the developer, of course, is that they get a steady, predictable, and constant stream of revenue out of it. It solves the problem of support: in olden dayes, customers would pay once, but would expect ongoing product support. Software firms would sometimes provide that support for free, which could hurt their bottom line if support costs weren’t factored into their asking price, or they would charge extra money for support credits, which is a hard sell to angry customers who are already struggling with the software. A constant monthly revenue stream means that developers can financially justify taking those support requests. SaaS also fills the company coffers so that developers can, theoretically, tweak and update their products on a regular basis. This means that instead of waiting for (and sometimes paying for) point releases, customers can enjoy ever-improving rollouts of their software.

The model works well with certain types of software. Accounting software like Xero and QuickBooks has to be constantly updated because of the shifting sands of tax collection. It was excruciating waiting for point updates to programs in the Adobe Creative Suite, which were often rolled out as separately billed releases.

Let’s be real: there’s nothing quick about doing your taxes.

But now, the SaaS genie is out of the bottle. Just as many game developers feel pressured to tune their games for microtransactions because common wisdom has it as the “only” way to make money, developers of “serious” apps have gone whole-hog on subscription models to the point where it’s unnecessary, and amounts to obvious gouging. And me? I’m getting off that merry-go-round.

Stopping the Drip

It’s telling to go through your corporate finances to discover just how insidious SaaS is. Software that seemed like a good deal at the time – only a couple of bucks a month – compounds program after program, to take a serious bite out of your operational costs. Over the past year, I’ve taken a very serious look at the number of SaaS to which I subscribe, and wherever there was a pay-once option for an equivalent program, I’ve gone for it.

The final straw that turned me into a crusader against SaaS was an app called Any.Do. It’s a simple todo list: create items, cross them off the list. It’s nicely designed and lovely to use, and I’d happily pay a few bucks for it.

(Call mom and apologize for what? Your extortionate business model?)

But a few bucks isn’t enough these days. The SaaS serpent slithers up and whispers in developer’s ears: how can you sssssqueeeze a few more buckssss from people?

Any.Do synchronizes your todo list across multiple devices. That means the developers have to maintain a server to store that information (or, more likely, they have to pay fractions of pennies to rent server space from Amazon). Any.Do also has a nice feature where, at the beginning of the day, you sit down and the app walks you through your todo list. With each item, you can choose to finish it today, tomorrow, or at a later date. The developer calls these little sit-downs “moments.” The catch is that these “moments” are usage-limited. Your initial install gets you about a dozen of them, but once they run out, you need a Premium account to get more moments.

What does that cost? Well, a Premium account with Any.Do is yours for the low, low price of $3.49 a month.

Cloud Competency

The value of a program that requires server interaction is arguable. Todo lists, being text, are absolutely tiny, and so the amount of data Any.Do is pushing around on your behalf is miniscule.

But it’s in the cloud, and the cloud costs money, right? Sure it does. That’s why i pay money to Google to store things in my Drive account, to Amazon for my S3 account, and to Dropbox for additional, accessible cloud storage. In the case of Dropbox, cloud storage is their entire business, and so (for good or for ill), i’m trusting them to get it right. Any.Do isn’t a cloud storage company. These guys have built a front-end software solution for daily todo lists. My preference is to trust Dropbox with the storage aspect, and Any.Do with a nicely designed app.

That’s why, instead of SaaS, i much prefer pay-once apps that sync my tiny data to my Dropbox account. That’s the model used by some of my favourite software like RecipeBook, Songbook, and You Need a Budget, all of which charged me some upfront buckazoids, before syncing my data to Dropbox and refrained from making monthly dips into my checking account.

Charging for “moments” in Any.Do is, in my opinion, impossible for the developers to justify. This is a core feature of the software which just works, by design. No server costs are charged to the developers when the moments feature is activated. What they’ve done is hobbled the functionality of their software and attached a price tag to it. That’s pure, unbridled, Scrooge McDuckian-level greed.

Toying With My Bank Account

It’s very much like the trend in video game software to lock a bunch of content on a disc, and charge people to access it piecemeal. Skylanders kicked off this trend: the game disc contains all kinds of characters, locked away to the player, who must pay ten bucks a pop for figurines to unlock the model or game mode already present on the disc.

Toy or statue? Them arms don’t bend.

Maybe it’s just my preference, but the “toys” don’t hold a lot of appeal for me – from Skylanders to Disney Infinity to Amiibo, they make attractive statues. But to justify its price, a ten dollar toy should be articulated with a few accessories and a comic book in the blister pack and some ever-loving kung fu grip for mercy’s sake. Can a brother get an amen?

Magnetic hat, articulated arms and legs, accessory piano, stability stand: this, my friends, is a TOY.

Microtransactions are skeezy, and i no longer play games that use them. Toy-unlocked video game content is skeezy, and i choose not to engage. And the third model in this unholy trinity is Software as a Service. P.T. Barnum’s worldwide army of suckers can fall for that kind of nickel-and-diming, but i’m voting with my wallet on this one: I’m sticking to pay-once software that syncs with existing specialized cloud services with no additional monthly cost, pining for the day we’ll see an end to the trend of Software as a Scam.

Shut up and listen. It won’t be long before Google Play or iTunes introduce an SaaS subscription library, SaaSaaS. Pay $9.99 per month for access to the unfettered versions of all participating apps. Apps that participate get a minuscule slither of that $9.99 based on usage; apps that don’t participate get even less because people will soon stop paying for anything that’s outside the library. Spotify for SaaS apps.

Very, very interesting. Something’s gotta give, for sure, because people can’t withstand the nickel-and-diming of Everyone and Their Dog demanding $nothing-ninety-five a month for their tiny apps.