It was especially challenging to write a job post for a position i needed to fill that not only didn’t exist yet, but that has never existed.

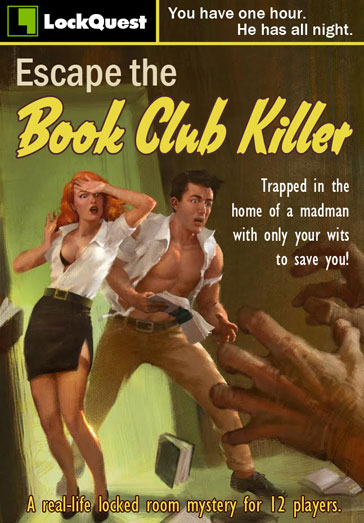

My new business, LockQuest, is an escape the room company. You buy tickets online, and then get locked in a room (in real life) for an hour. You collect clues and solve puzzles to escape, just like in the virtual versions of these games.

But as i’ve discussed in a previous article, there are some crucial, game-changing differences between virtual games and games that transpire in meatspace. One of the biggest pressures that i face as an escape game owner is ensuring that my players have a great time, and i firmly believe that has a lot to do with how successful they feel when time is up.

Welcome to Our Game. You Already Suck.

i’ve played more than a few escape games where they really tout their win/lose ratio. “Only 3 percent of players have ever finished our game” they say, lighting a cigarette like that dangerous kid who lived up the street and who got to take time off school to visit his mom in prison. “Think YOU’LL do any better?” And then they blow smoke in your face. And you sit there thinking “Yeah … YEAH! i’m WICKED smart! i bet i’ll beat ALL those other chumps!”

It’s not until you reach the end of the hour that you realize why there’s such a low success rate: it’s often down to shitty puzzle design. Most games (including ours) leave the biggest, beefiest puzzle until the end of the game. But while i feel our final puzzle is fair and logical, i’ve played games that take such a prancy leap in logic, require such a minute attention to detail, or break a game rule so erroneously, that player failure is largely the fault of the designers.

No Clue

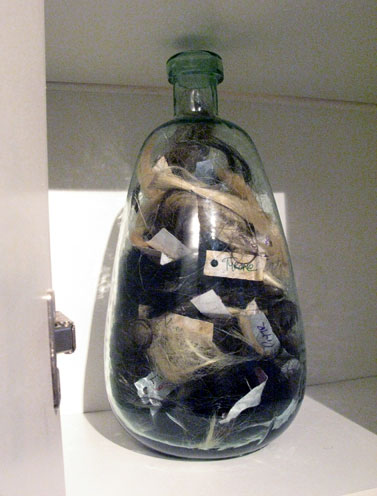

As we playtested Escape the Book Club Killer, another challenge arose: players weren’t just getting stuck on the big, juicy parts of the game. They were getting stuck on small things – an unopened drawer here, an undiscovered prop there. Not to give too much away, but one of our props is a giant jar filled with human hair. We saw one team member open the cupboard, take the jar off the shelf, look at it quizzically, and then put it back on the shelf. And for the remainder of the game, no other team members were thorough enough to open that same cupboard.

One game prop that wound up being crucial to solving this problem is our phony phone. The old-fashioned rotary dial phone allows players to dial 4-1-1 to reach a LockQuest staff member in our foyer. But more importantly, staff members can call into the room to offer hints.

The biggest difference between LockQuest and other escape game companies is that we go out of our way to make players feel smart and successful. We could just call into the room and say “hey. Go pick up that giant jar of human hair. It’s important.” But that would make players feel dumb as a stump.

Is Your Refrigerator Running?

Instead, we call into the room as various characters. These characters are largely improvised on the spot, based on whatever block is preventing players from progressing. So if the players haven’t fished the engagement ring out of the u-pipe in the sink (not a real puzzle), we’ll call in as Julie the plumber.

“Hi! It’s Julie. i was just there working on your sink last week, and – gosh, i feel so embarrassed about this – i think i might have lost some jewelry in there. Imagine! You hire a plumber, and she winds up clogging your pipes! Ha! Anyway, if you could fish it out for me and set it aside, i’d be super grateful. i can drop by tomorrow to pick it up. THANKS BYE!!!”

When we handle it this way, the player feels much less hand-held. Even though the players have missed something, the themed phonecall feels like it’s part of the game, like it’s planned. The calls help us get players past sticking points still feeling smart and successful, and we have a great time improvising the call. It’s a win/win.

It doesn’t always work, mind you. One of the perils of improvising hints is that we could say the wrong thing and send the players spinning off on a pointless and unintended trajectory. In a recent game, we called in with a clue and made an off-hand comment about a window. The players all flocked to the window looking for something important. In another case, i told players to change a computer password from (WHATEVER) to something with 16 digits, 5 capitals, 9 special symbols, and an uppercase “G”. Instead of punching in (WHATEVER), players chose to focus on those implausible ad-libbed password requirements.

Fake It ‘Til You Make It

With all this mind, i knew i wanted LockQuest hosts to possess two important skills: customer service, and improvisation. And technically, that’s only one skill … if you’re a good enough improv actor, you can pretend to be the best damned customer service expert on the planet. This is part of the strategy behind Disney calling their employees “cast members” – employees don’t have to actually be happy and helpful … they just have to act happy and helpful. That way, it doesn’t matter if an employee has had a bad morning: when you work for Disney, this is how you act.

It’s not nearly as cynical as it sounds. If you know much about psychology, you know that we tend to become what we practice. Fake being happy and helpful long enough, and you’ll actually become happier and helpfuller.

Job Interview Do’s & Dragont’s

Putting those improv chops to the test became far more important than i’d ever imagined. It was immediately obvious who had the knack, and who didn’t. In an incredibly unexpected turn, one successful candidate lauded his D&D dungeon mastering skills during the interview. Ordinarily, that kind of thing would be Job Interview Suicide.

Oh – you say you’re a LARPer?

In this case, and in probably No Other Job Ever, it actually made sense. i had explained to the candidate that every group of players was different, and that our playtesting teams were all getting stuck in different places. Some would ignore the giant jar of human hair. Some wouldn’t open a particular desk drawer. Others wouldn’t fish around in the pockets of the overalls. Still others wouldn’t make the connection between the Big Red X on the carpet, and the Big Red X on the sheet of paper (which also has a picture of a carpet on it, and is labeled “carpet”).

“It’s like D&D!” he enthused. “Do you know anything about D&D??”

“You spend all this time setting up a campaign, and you want your players to go through and experience all the cool stuff you’ve got planned, but sometimes they need nudges here and there so you can make sure they’ll have the best adventure possible.”

Hmm. (Retract finger from ‘security’ call button.) Keep talking, kid.

+3 to Employment

He’s absolutely right. When you run real escape games with a team’s happiness as your goal, they have a lot more in common with classic pen-n-paper tabletop games than with video games. Many video games are all about punishing players, while poorly-designed online escape games are about how much smarter the developer is than you. Both of these traits contribute to a bad experience for all but a certain type of achievement-focused player (Dark Souls fans, for example), and both of these traits have unfortunately carried over to live escape-the-room games needlessly.

The hosting job at LockQuest, consequently, is wonderful. Our goal is to make players feel like they’re in an intimate, friendly, and fun setting. Once players enter the room, we co-hosts begin closely monitoring players over four CCTV cameras and listening through headphones. Then the play session turns into a DM-like experience, with both co-hosts taking turns calling the room with outrageously improvised character voices. In a recent game, i called in as “M.C. Clue” and rapped a hint to the players. My co-host likes to call as the sexually-repressed neighbour who’s constantly “worried” she’s being spied on in her underthings.

Basically, the job boils down to this: make friends of the players, make prank calls to the room, and make sure the bathrooms are clean before the next game. What a great gig.

i’m incredibly happy about how it’s worked out. It’s like i’ve rolled a natural 20 for “job.”

Come Get Killed at LockQuest

Tickets are now on sale for our debut game Escape the Book Club Killer at LockQuest.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks